Animal cancer information

Find the resources you need here

We have been working hard to write, collate and update a range of resources and animal cancer information for pet owners and veterinary practices alike. With this information, our readers can educate and inform themselves on the available options for treating pet cancer and finding the best pathways for treatment too. We are also keen to help pet owners understand the journeys that other pet owners have been through so they know what they may expect to experience with their own pet.

Scroll down this page to find:

- Downloadable information sheets

- Map of veterinary practices with expertise in

diagnosing and treating cancer

- FAQ's can be found at the bottom of this page

Information Sheets for Owners

Downloadable pages

Types of Cancer

General information about the various types of cancer.

Screening Skin Masses with HT Vista

End of Life, Pet Loss and Grief Support

With links to further resources on pet loss and grief

Case studies

stories of cases to provide an insight into the journey that owners and pets experience in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

Vet Practices Supporting Your Pet's Cancer Journey

A list of practices and referral centres with knowledge and experience in pet cancer diagnosis and treatment. Click on the square in the upper right hand corner to enlarge the map. Practices with a red pin have radiotherapy facilities in addition to offering chemotherapy and surgery for cancer treatment; purple pins offer chemotherapy and surgery and blue pins indicate practices that offer surgical oncology services. If you think that your practice should be included on this map, please contact us at hello@actcharity.uk so we can update our map.

FAQ's

Get in touch

You can find information and advice on animal cancer support here, or feel free to contact us directly:

Call: 07376 213733

Email: hello@actcharity.co.uk

What is neoplasia

- When we talk about lumps, growths or tumours we are usually talking about neoplasia.

- A neoplasm is a bunch of cells that forms a lump or tumour and it is the result of uncontrolled growth of cells.

- This may be due to a mutation or a lack of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

- A neoplastic mass is also called a tumour and it may be

- benign

- malignant

What is a benign tumour

- When we talk about lumps, growths or tumours we are usually talking about neoplasia.

- A neoplasm is a bunch of cells that forms a lump or tumour and it is the result of uncontrolled growth of cells.

- This may be due to a mutation or a lack of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

- A neoplastic mass is also called a tumour and it may be benign or malignant

What is cancer

- Cancer is the common name given to all the various forms of malignant neoplasia.

- A tumour is a mass of cells that are growing out of control. There are two main types of tumours:

- Malignant tumours or cancers and benign tumours.

- As a general rule, malignant tumours (cancers) are more life threatening than benign tumours because of the risk of spread throughout the body.

Why is malignant neoplasia called cancer

- Malignant tumours are the most aggressive types of neoplasia as they tend to grow by invading into the surrounding tissues.

- This may cause direct effects such as pain, inflammation or ulceration, depending on which part of the body is involved. They also have the ability to spread to other parts of the body (metastasis).

- This ability to spread and produce secondary tumours makes them potentially life threatening.

- Secondary tumours can occur anywhere in the body with the most common sites being the lymph glands and the lungs although they can also occur in the liver, kidney, brain and bones.

How are cancers named

Most malignant neoplasms are named for the cell type, tissue or body organ from where they start.

Malignant neoplasia tends to be named by the site or location or organ affected, and the name ends with either the word –‘sarcoma’ or ‘-carcinoma’.

Examples include:

- Bone cancer starts in a bone and is called osteosarcoma

- Liver cancer starts in the liver and may be called hepatic carcinoma or adenocarcinoma depending on the cell type

- Lymphosarcoma is sometimes called lymphoma even though it is a malignant neoplasia that starts in the lymphatic system

- Fibrosarcoma is a malignant tumour of the fibrous connective tissue

- Liposarcoma is a malignant tumour of the fat tissue

Melanoma is usually malignant and, even though its name suggests it is benign, is more appropriately called Malignant Melanoma.

What should I do if I find a lump on my pet

Not all lumps and bumps turn out to be tumours, but it is important to ask your vet to have a look at it when you first notice one, in order to make a diagnosis.

Your veterinary surgeon will perform a physical examination and may carry out laboratory tests, imaging studies and/or recommend a biopsy or needle aspirate

- In most cases, a biopsy is the only way to know for certain whether cancer is present.

- During a biopsy, the veterinary surgeon removes a small sample of tissue from the abnormal area.

- A pathologist then studies the tissue under a microscope to identify cancer cells. This is the most accurate method of diagnosing cancer

There are many different types of tumours and the treatment for each can differ. To ensure the most effective treatment is given and to get an idea of the likely outcome an accurate diagnosis is needed to determine the exact nature of the lump or tumour type.

“Let’s wait and see” is not a good option in most cases as it is much easier to remove a small mass that is detected early. In many cases, complete surgical removal of a mass can be curative.

Why is early diagnosis important

There are many different types of tumours and the treatment for each can differ.

- An early accurate diagnosis gives the best chance for appropriate treatment early on, before the disease progresses or spreads.

- A small tumour, even a malignant one (cancer), is more likely to be cured if it is treated early.

A wait-and-see approach is best avoided as most tumours do not disappear and will continue to grow.

- If this approach is considered, it is important to measure all dimensions of a lump and monitor it carefully for any changes. A set of calipers (include an image) can be used to accurately measure the size of a lump.

To ensure the most effective treatment is given and to get an idea of the likely outcome, a biopsy or needle aspirate will be needed.

- In most cases, a biopsy is the only way to know for certain whether cancer is present.

- During a biopsy, the veterinary surgeon surgically removes a small sample of tissue from the abnormal area.

- A pathologist then studies the tissue under a microscope to identify cancer cells.

What are the clinical signs of cancer in pets

Clinical signs of cancer are often vague and non-specific; however, many animals can also seem to be perfectly well.

The most common signs include:

- Abnormal swelling or lump that grows

- Sores that do not heal

- Loss of appetite or increased drinking

- Offensive breath

- Unexplained loss of weight

- Difficulty eating or swallowing

- Persistent lameness or stiffness

- Difficulty breathing, urinating, or defecating

- Breathlessness or loss of stamina

- Bleeding or discharge

These signs may also occur in other non-cancer conditions such as inflammation, infection, benign growths or other problems.

It is important to take your pet to see a veterinary surgeon in order to obtain a diagnosis of cancer

How do tumours affect animals

- This depends upon the type and location of the tumour. The clinical signs will vary with these factors.

- When small, many tumours do not cause a problem and it may be only when the tumour is large that it has an effect on an animal.

- There are many different types of tumours and each behaves in a slightly different way.

- It is therefore important to have a sample of the tumour sent for examination by a specially trained veterinary pathologist at an external laboratory.

Does cancer always cause pain

Having cancer does not always mean having pain. Whether a patient has pain may depend on the type of cancer, the extent of the disease and the pet's tolerance for pain. Most pain occurs when the cancer grows and presses against bones, organs, or nerves. Pain may also be a side effect of treatment. However, pain can generally be relieved or reduced with prescription medicines recommended by your veterinary surgeon.

How is cancer diagnosed

- If your pet shows one or more clinical signs that may suggest cancer, your veterinary surgeon will need to find out whether it is due to cancer or to some other cause.

- Your vet will take a history of your pets illness and perform a thorough physical examination and may order laboratory tests, imaging studies and/or recommend a biopsy.

- At this point, your vet will have a list of possible conditions in mind (differential diagnosis) that could be causing your pets illness.

- In most cases, a biopsy is the only way to know for certain whether cancer is present.

What is a differential diagnosis

- A differential diagnosis is often a list of two or more conditions.

- Creating a list of differential diagnoses involves a process of differentiating between conditions which share similar history and clinical signs

- This process results in a list of the possible conditions that might produce the observed clinical signs.

- Generating a differential diagnosis is an important part of clinical reasoning. It enables appropriate testing to rule out possibilities and confirm a final or definitive diagnosis.

- Note: When lumps, bumps and enlarged lymph nodes (glands) are found in a cat, there are more non-cancerous disease possibilities or differential diagnoses than for dogs. As a result of infection or reactive inflammation, cats can develop markedly enlarged lymph nodes which can make the diagnosis of cancer more difficult.

What laboratory tests

- Tests of the blood, urine, or other fluids can help veterinary surgeons make a diagnosis.

- Examples include:

- CBC – a complete blood cell count of the red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

- Chemistry screen – a panel of tests that includes electrolyte levels (sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium and phosphorus), urea, creatinine and liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALKP)

- Urinalysis – an analysis of the specific gravity (concentration) of urine as well as presence of any cells, blood and protein.

- These tests can also give an indication of how healthy your pet is by demonstrating how well the body organs (such as the kidneys or the liver) are performing their functions.

- Also, high amounts of some substances (such as calcium in the blood) may be a sign of cancer.

- However, abnormal lab results are not a sure sign of cancer and veterinary surgeons cannot rely solely on laboratory tests to diagnose cancer. (link to How is cancer diagnosed?)

- Sometimes the tests will show the presence of cancerous cells.

What about imaging studies

- Imaging procedures create ‘pictures’ of areas inside the body that help the veterinary surgeon see whether a tumour is present. These images can be obtained in several ways:

- Radiographs (x-rays): The most common way to view bones and organs inside the body.

- They allow us to see the outline of an organ but may not tell us what is going on inside it.

- A radiograph creates a 2-dimensional picture so several radiographs may need to be taken from different directions to know where a lesion is located.

- Ultrasound: An ultrasound device sends out sound waves that people cannot hear.

- The waves bounce off tissues inside your body like an echo.

- A computer uses these echoes to create a picture called a sonogram. This allows to see inside an organ.

- MRI: A strong magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of areas in your body.

- Your veterinary surgeon can view these pictures on a monitor and can print them on film.

- MRI or magnetic resonance imaging is most useful for the brain and spine.

- CT scan: An x-ray machine that takes 3-dimensional image by taking many pictures from many different directions feeds these images into a computer to produce a more detailed picture of the body in cross section.

- CT or computed tomography scans are useful in detecting cancer, diagnosing lung and chest problems and identifying bone injuries.

- They can detect smaller lesions that radiographs but are significantly more expensive.

- Your pet may receive a contrast material (usually by injection) to make x-rays, MRI images and CT scans easier to read.

- It is important to remember that not every case needs to undergo every type of imaging available and there is no point in having some very good images of a tumour with no finances left to pay for treatment.

- The type of imaging that is appropriate for diagnosing cancer depends on the likely differential diagnoses that your vet is considering.

What is a biopsy

- In most cases, your veterinary surgeon will need to perform a biopsy to make a diagnosis of cancer.

- During a biopsy, a sample of the lump or tumour tissue is removed and sent to a diagnostic laboratory where a vet with specialist training in cytology and/or histopathology will look at the tissue under a microscope to identify cancer cells.

- A sample of cells or tissue may be obtained in several ways:

- With a needle: The veterinary surgeon uses a needle to withdraw tissue or fluid. This is often referred to as a fine needle aspirate or cytology sample.

- With an endoscope: The veterinary surgeon uses a camera in a thin, lighted tube (an endoscope) to look at areas inside the body. The veterinary surgeon can remove tissue or cells through the tube.

- With surgery: Surgery may be excisional or incisional.

- In an excisional biopsy, the veterinary surgeon removes the entire tumour, often with some of the normal tissue around the tumour (called a margin).

- An incisional biopsy involves removing a small part of the tumour and is more common in tumours which are large or in a difficult location.

- The type of biopsy taken will depend on the location and suspected type of tumour.

- A biopsy must be planned in advance and is usually best performed before any attempt is made to remove the tumour.

- Contrary to popular belief, taking a biopsy does not increase the risk of spread if performed correctly.

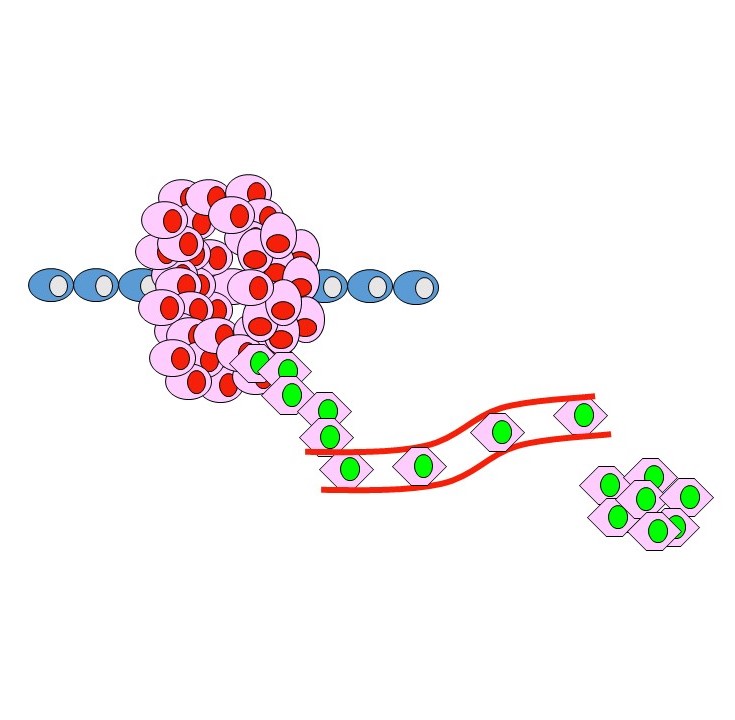

What is metastasis

- Metastasis is the presence of cancer tissue away from the original (primary) site of the tumour.

- It occurs when cancer cells break away from the primary tumour, enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system and form new tumours in other organs. It’s a bit like sowing seeds - some may take and grow others may not.

- The new tumours are called secondaries and they will have the same type of abnormal cells and the same name as the primary tumour.

- For example, if bone cancer spreads to the lungs, the cancer cells in the lungs are actually bone cancer cells. The disease is called metastatic bone cancer and not lung cancer.

- The new or secondary tumour is called ‘distant’ or metastatic disease.

What is a secondary tumour

- A secondary tumour is a mass of cancer cells separate from the primary tumour that is a result of spread called metastasis.

- The type of primary tumour helps to predict the location and risk of a patient developing secondary tumours.

- Imaging studies such as X-rays, ultrasound scans and CT or MRI scans can be used to look for secondaries.

- However, even if no secondaries are initially seen, this is no guarantee that they will not develop at a later date.

- A secondary tumour starts as a small ball of cells less than 100th of a millimetre (<0.01 mm) and it must grow to a size where it can be detected.

- A mass as small as 1-2 mm is visible on a CT scan

- A mass needs to be about 5-10 mm or larger to be visible on a radiograph (x-ray)

- Secondaries can occur when the original primary tumour is still small (Figure 1).

- Sometimes the presence of secondaries are the only indication that the patient has cancer and it can be hard to find the primary tumour which may be very small.

- Secondaries that appear after a primary tumour has been surgically removed will have been present at the time of surgery but were just not detected at that time as they were too small to find.

- For tumours with a high likelihood of secondary spread, anticancer drugs (chemotherapy) or radiation therapy may be recommended after surgery to delay or even prevent secondaries.

- However, not all tumours are sensitive to these treatments.?

Figure 1. Metastasis occurs when cells from the primary tumour (red) break away and travel to another site to form a secondary tumour (green).

Why is metastasis important

- Metastasis occurs with malignant tumours; however, not all malignant tumours will undergo secondary spread.

- Some cancers, often referred to as low grade, have a low metastatic rate and this means that only a small percentage actually spread.

- For example, malignant tumours arising from fibrous tissue in the skin of dogs (known as fibrosarcomas) are generally low grade and <15% will metastasise.

- At the other extreme there are cancers with a high metastatic rate where most will spread. Bone cancers in dogs (osteosarcoma) are ‘high grade’ and at least 95% will metastasise.

- However, it is not always possible to predict which patients will experience spread of their disease.

- Metastatic spread is the most difficult type of cancer to treat and, as the metastases grow, they take over more of the patient’s normal organs.

- For example, secondary tumours growing in the lungs will reduce the function of the lungs such that the patient cannot get enough oxygen and tires easily.

- As the tumours grow further, coughing and general illness may also become apparent.

- The clinical effects of the spread will also depend on where they are growing.

- Patients with spread close to the main airways may cough even when the tumours are relatively small, whilst others with spread to the lung tissue may have no clinical signs until the lungs are almost completely taken over by tumour tissue.

What happens after a diagnosis of cancer is made

- Your vet will discuss with you the diagnosis and type of cancer as well as the prognosis and management plan (Link to related questions on treatment).

- To help remember what you are told, you may wish to take notes or ask whether you may record the conversation.

- Some people also want to have another family member or friend with them when they talk to the veterinary surgeon.

- They may take part in the discussion, take notes, or just listen with you.

- You do not need to ask all your questions at once.

- You will have other chances to ask the veterinary surgeon or nurse to explain things that are not clear and to ask for more information.

- Your veterinary surgeon may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral.

- Specialists who treat cancer include surgeons, medical oncologists and radiation oncologists.

- The treatment plan depends mainly on the type of cancer and the stage of the disease.

- Veterinary surgeons also consider the patient's age and general health.

- Sometimes the goal of treatment is not to cure the cancer but to maintain as normal a quality of life as possible in your pet for as long as possible.

- In this case, the goal is to control the disease or to reduce clinical signs associated with the cancer for as long as possible.

- The treatment plan may change over time.

- Before starting treatment, you may want another opinion about your pet’s diagnosis and treatment plan. A second opinion is usually sought when there is doubt about the diagnosis or treatment whereas a referral is usually to seek specialist management of the case.

Can cancer in pets be treated

- There are many different types of tumours and the treatment for each will differ.

- To ensure the most effective treatment is given and to get an idea of the likely outcome an accurate diagnosis is needed.

- This is usually best performed before any treatment is begun.

- There have been major advances in the treatment of cancer in humans and many new medicines and techniques can be used in pets too.

- There are 3 major forms of treatment: surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

- Surgery remains one of the best ways to treat most tumours and in many cases can be curative.

- However, surgery must be bold and well planned; any tumour cells left behind will cause the tumour to grow back.

- Surgery may be used with adjunctive radiation or chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy or radiotherapy can be useful to treat a variety of tumours, particularly some of those that occur in the mouth, nose, skin and brain.

- Certain tumours can be cured, some have their growth slowed and some, unfortunately do not respond at all.

- Anti-cancer drug therapy (a form of chemotherapy) can be used against some tumours (especially leukaemias and cancer of the lymph glands [called lymphoma, but it actually lymphosarcoma]).

- The doses used in animals are carefully calculated to aim to avoid unpleasant side effects.

- For this reason, most forms of chemotherapy used in veterinary medicine are considered to be a form of palliative therapy rather than curative although we can achieve good periods of remission with a return to a good quality of life in some cases.

- Referral to a specialist centre for treatment may be necessary for more advanced treatments.

- Specialist centres will have oncologists that are veterinary surgeons that specialise in diagnosing and treating cancer.

Is my pet too old

- It is often said of people that you are as old as you feel – this is equally true of animals.

- If an individual is healthy and active, their age should not be a barrier to treatment.

- Treatment is aimed at prolonging a good quality of life for as long as possible.

- One way to think about this is that one extra year for a 10-year-old dog is 10% of its life.

- While cancer is more common in older pets, age alone is not a major factor when considering whether to treat.

- If it were not for their tumour, many older pets are otherwise healthy individuals.

- Some pets can be young in years but seem old, whilst some older pets can still seem extremely youthful.

- One of the best indicators of outcome (prognosis) for many cancers is response to initial treatment.

- Also, just because you decide to start a course of treatment, this does not mean that you obliged to complete the course of treatment.

- Circumstances often change and treatment decisions can be changed at any time.

How is cancer in pets treated

- Just as in people, there are 3 major forms of cancer treatment:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Used alone or in combination.

- Surgery can often be curative if performed early enough.

- Radiotherapy and chemotherapy can be used to increase the chances of cure but are more often used to achieve periods of remission with a return to a good quality of life.

- Whether to treat a pet with cancer is an important decision and needs to take into account many factors including any concurrent illness (such as coexisting kidney or heart failure), quality of life for the pet, with or without treatment, logistical implications and finances.

- If remission or a cure is unlikely, palliative therapy to make the pet more comfortable without a curative intent can prolong good quality of life while owners come to terms with end of life decisions.

Is cancer treatment worth doing

- As in people, cancer is treatable and is even curable in some cases.

- Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are the keys towards a successful outcome.

- Your pet cannot choose what cancer they will get but you can choose the best course of action taking into account your pets personality and your needs and limitations.

- Many neoplasias, including a number that are malignant, can be cured if caught early.

- Some tumours, whilst not curable, may be kept under control for some time allowing the pet to enjoy a normal, happy quality of life.

- Unfortunately, some tumours are too advanced for any treatment and then euthanasia may be the kindest option.

- Veterinary surgeons may use one method or a combination of methods to treat cancer, depending on several factors, including:

- Type and location of the cancer

- Whether there is spread of the disease

- Patient's age and general health

- Since treatment for cancer can also damage healthy cells and tissues, it can cause some side effects.

- People often worry that the side effects of treatment are worse than the disease.

- Owners and veterinary surgeons should discuss the treatment options, weighing the likely benefits of killing cancer cells and the risks of possible side effects.

- Veterinary surgeons can suggest ways to reduce or eliminate problems that may occur during and after treatment.

- Many owners want to take an active part in making decisions about their pet’s medical care and it is natural to want to learn all you can about your pet’s disease and treatment choices.

- However, it is often difficult to take in everything that your veterinary surgeon says after the diagnosis is made.

- It often helps to make a follow-up appointment and to prepare a list of questions before the appointment.

What is palliative therapy

- Palliative therapy is often used to make your pet more comfortable when the chance of achieving a remission or a cure is unlikely.

- Surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy can all be used as a form of palliative therapy when there is not a curative intent.

- It can prolong good quality of life while you come to terms with end of life decisions.

- Chemotherapy given at the carefully calculated doses used in most of our pets to avoid the most serious side effects is a form of palliative therapy that can result in periods of remission with a return to a good quality of life in some cases.

- Palliative care involves using medication to relieve pain and discomfort, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) such as meloxicam, opioid pain relievers, steroids such as prednisolone and sometimes local anaesthetics.

- It may also involve giving anti-nausea medication or appetite stimulants.

- Palliative care can make your pet more comfortable, giving you an opportunity to spend some quality time with your pet and make the most of the time they have left.

- Owners often comment on how much of a difference a little pain relieving medicine makes in making their pet more comfortable and even improving appetite.

- In most instances you should be able to arrange for palliative care in your home with the help of your veterinary practice.

What about nutrition

- Your pet needs enough calories to maintain a healthy weight.

- Your pet also needs enough protein to remain strong.

- Eating well may help your pet feel better and have more energy.

- Sometimes your pet may not feel like eating.

- They pet may be uncomfortable or tired or may find that foods do not taste as good as they used to.

- Warming the food or adding sauces and gravies may help increase intake.

- In addition, the side effects of treatment (such as poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, or mouth sores) can be a problem.

- If your pet is having trouble chewing and swallowing, you may need to give soft or blended food.

- Many owners want to know how they can help their pet fight cancer by eating certain foods or taking vitamins or supplements.

- Unfortunately, there are no studies that prove that any special diet, food, vitamin, mineral, dietary supplement, herb or combination of these can slow the growth of cancer or keep it from coming back.

- In fact, some products can cause other problems by changing how your cancer treatment works.

It is best to talk to your veterinary surgeon before putting your pet on a special diet or giving any supplements.

What about complementary and alternative therapy

- Some people with cancer use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

- An approach is generally called complementary medicine when it is used along with a standard treatment(s).

- An approach is called alternative medicine when it is used instead of standard treatment

- Acupuncture, massage therapy, herbal products, vitamins or special diets, visualization, meditation, and spiritual healing are types of CAM.

- In human medicine, many people with cancer say that CAM helps them feel better.

- However, there are no controlled trials in pets that show any benefit and some types of CAM may change the way standard treatment works; we often just do not know what effects or interactions may occur with herbal or other CAM therapies when an individual is undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Before starting these types of treatment for your pet, you should discuss this with your veterinary surgeon.

What is prognosis

- Prognosis is a term used to predict how long your pet may be free of disease or may survive.

- It is the likelihood or chance of recovery from a disease, based on the available evidence.

- Certain factors can affect the prognosis and treatment options, including age, general health, presence of concurrent conditions, whether this is the first diagnosis or recurrence, etc.

- Very few prospective studies have been published about pets with cancer.

- Therefore, most of the information available on how well animals do after being diagnosed with cancer comes from studies that follow a series of cases.

- Prognosis is usually expressed as a probability of survival sometime after diagnosis, such as a one-year survival rate being the probability of surviving for 1year from the time of diagnosis.

- Alternatively, prognosis can be expressed as the period of time that has passed until 50% of the patients are still alive, and this is the median survival time (MST) (link to What are cancer statistics?).

- Survival times are averages for that condition and don’t take into account your pets precise situation.

- For example, a 12 month average or median survival time may be made up of a group of animals that survive from 4 months to 18 months or from 8 months to 24 months.

- While it is often hard to predict the future for your pet, your vet will try and take all factors into account when

What is remission

- Complete remission (CR) is defined as when the tumour can longer be detected.

- This can be based on physical size of the tumour or by imaging with radiography or ultrasound.

- Unfortunately, complete remission is not the same as a cure.

- Generally, the smallest mass that can be detected by radiographs is about 0.5 cm, more sophisticated imaging can detect down to 0.25cm but this still represents approximately a million cells.

- Partial remission (PR) is defined as a reduction in size by more than 50%.

- Static or stable disease(SD) is defined as change in size (smaller or larger) of less than 25% and progressive disease (PD) is defined as increase in size of more than 25%.

- Using these definitions helps your vet to define the effectiveness of treatment or the next course of action.

What about follow-up care

- Advances in early detection and treatment mean that many people with cancer are cured.

- Unfortunately, cancer is often diagnosed relatively late in the course of the disease in pets.

- This is because the clinical signs are often vague, and animals are good at hiding them when they are sick.

- Unfortunately, cancer is often diagnosed relatively late in the course of the disease in pets.

- As veterinary surgeons, we can never be certain that the cancer will not come back once it has been treated.

- Undetected cancer cells can remain in the body after treatment.

- Although the cancer seems to be completely removed or destroyed, it can return.

- We call this a recurrence.

- Follow-up care means seeing a veterinary surgeon for regular medical check-ups

- Your pet's follow-up care depends on the type of cancer and type of treatment as well as your pet's overall health

- Follow-up care is usually different for each patient who has been treated for cancer.

- In general, patients usually return to the veterinary surgery every few weeks/months during the first few months after treatment and then less frequently after that.

- At these visits, your veterinary surgeon will look for side effects from treatment and check if the cancer has returned (recurrence) or spread (metastasis) to another part of the body.

- To find out whether the cancer has spread or returned, your veterinary surgeon may do follow-up laboratory tests and/or imaging studies.

- If your pet has a recurrence, you and your veterinary surgeon will discuss new treatment goals and a new treatment plan.

- During follow-up exams, your veterinary surgeon will also check for other problems, such as side effects from cancer therapy that can arise long after treatment.

- Check-ups help ensure that changes in health are noted and treated if needed.

- Between scheduled visits, you should contact the veterinary surgeon if any health problems occur.

- It is important to be able to talk openly with your veterinary surgeon.

- Both of you need information to manage your pet's care.

- Be sure to tell your veterinary surgeon if your pet is having trouble doing everyday activities and talk to our vet about any new signs to watch out for and what to do about them.

- If you are concerned that the treatment your pet had puts it at a higher risk for having other health problems, be sure to discuss this with your veterinary surgeon as you develop your pet's follow-up plan.

- At each follow-up visit, it is a good idea to mention any health issues your pet is having, such as:

- New signs of illness or pain

- Physical problems that get in the way of daily life or that bother you, such as tiredness or weight gain or loss

- Other health problems your pet may have, such as heart disease, diabetes or arthritis

- Things you want to know more about, such as new research or side effects.

- Just because your pet has certain signs, it doesn't always mean the cancer has come back.

- Signs can be due to other problems that need to be addressed.

What about the future

- Just because your pet has certain signs, this doesn't always mean the cancer has come back.

- Signs can be due to other problems that need to be addressed.

- The term "cancer survivor" is used to include anyone who has been diagnosed with cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the rest of his or her life.

- Family members, friends and other pets are also part of the survivorship experience.

- While the word may seem strange and you may feel that it does not apply to your pet, the words 'survivor' and 'survival' can help many people think about how they can support their pet living with cancer and even about life beyond the cancer.

- While cancer is a major event for all whose pets are diagnosed, it brings with it the chance for growth – an opportunity to deepen relationships among family members and the pet.

- As hard as treatment can be, many owners of cancer survivors say that every additional day they had to spend with their pet was worth it. Many say they have drawn from their experience to help other pet owners or to become advocates to improve cancer research, treatment and care.

- The end of cancer treatment is often a time to celebrate.

- You may feel relieved to be finished with the demands of treatment and visits to the vet but, at the same time, you may be worried. It's common to be concerned about whether the cancer will come back.

- When treatment ends, you may expect life to return to the way it was before your pet was diagnosed with cancer.

- But it can take time to recover. Your pet may have permanent scars or may no longer be able to do some things. People who have gone through cancer treatment describe the first few months as a time of change.

- It's not so much 'getting back to normal' as it is finding out what's normal for your pet now. You can also expect things to keep changing as your pet's recovers. The new 'normal' may include making changes in the way your pet eats and the things they can do.

- All cancer survivors should have follow-up care. Knowing what to expect after cancer treatment can help you and your family make plans, lifestyle changes, and important decisions.

- Some questions you may have after treatment include the following:

- Should I tell the veterinary surgeon about signs that worry me?

- Which veterinary surgeons should I see after treatment?

- How often should I see my veterinary surgeon?

- What tests do I need?

- What can be done to relieve pain, fatigue, or other problems after treatment?

- How long will it take for me to recover and feel more like myself?

- Is there anything I can or should be doing to keep cancer from coming back?

When is it time to say good-bye

- For many patients, their cancer will result in their death. While we would all like our pets to die in their sleep, this is extremely uncommon and most pets who die naturally suffer pain and discomfort at the end. Euthanasia is the final gift we can give our much-loved pets when the time is right. The challenge is that it can be hard to know how soon that time will come. Its rather like being on a slope halfway up a mountain– you know that at the end you will be at the bottom of the mountain, but you don't know how steep that slope will be. The speed of deterioration can also change. Knowing that your pet has a cancer which will ultimately be the reason that you need to let him/her go is very difficult. It is emotionally exhausting for everyone involved in the care of that pet. However, it also gives us the chance to plan their end of life so that their final day is as good as it can be.

- For many pets with cancer they are otherwise well but the location of the cancer means that one aspect of their life is poor. As a pet owner, you know your pet better than anyone and, in most cases, will know when it is time to let them go. However, if you are not certain you will know then talk to your vet about things to look out for. Generally, most of us feel that it is better to let a pet pass away before their quality of life is seriously affected. Pet owners rarely say that they wished they had waited longer to make a decision about euthanasia; most will say that they wished they had decided sooner rather than later.

- When making end of life decisions, there is a lot to think about including:

- Whether you would like to have euthanasia performed at home or at the vets. Many vet practices have a special room where they will meet with you to discuss and perform the procedure.

- Does your pet have a favourite place, food or activity that you would like him/her to be able to experience on its final day?

- Who needs to say goodbye and who wants to be present during the euthanasia procedure?

- What would like to happen after your pet has passed away?

- Do you want any mementos such as hair or paw prints?

- Do you want to have your pet cremated or would you prefer to have them buried?

- Do you want to have an individual cremation and get your pets ashes back to keep or to scatter at a place that was special for you both?

- It can be helpful to start to have conversations about these issues well in advance of your pets final day.

- Keeping a note of the things you will need or want for that day makes it easier to remember them when the day comes as you are undoubtedly going to be upset and find remembering the plans you made difficult.

- After your pet has passed away it is natural to feel grief. This may manifest as anger, guilt and/or sadness.

- Grief varies widely, with some people feeling affected for a prolonged period and others seeming to recover quite quickly. It can resurface at any time in the future.

- There is no right way to grieve the loss of your pet but there are organisations that can support you during the grieving process. Society as a whole is starting to appreciate how the loss of a pet can be at least as difficult or sometimes even worse than the loss of a family member.

What is the scientific basis of cancer and why does it occur

- Cancer begins with the basic unit of life for the body: cells.

- Every cell of the body is normally under very strict control with a defined life span and role.

- A group of cells forms a tissue and a group of tissues forms an organ in the body.

- Cells normally divide and grow to form new cells as the body needs them.

- When cells grow old and die, new cells take their place.

- This process may go wrong when the genetic material (DNA) of a cell becomes damaged or changed, producing mutations that affect normal cell growth and division.

- When this happens, new cells are formed that the body does not need or, alternatively, old cells do not die as they normally should through programmed cell death (apoptosis).

- These extra cells can form a mass of tissue called a growth or tumour.

Why does it occur?

- Cancer results when changes occur in genes that control normal cell division and death (called mutations).

- Very occasionally, a cell acquires the ability to divide and grow outside this normal control and a cancer develops.

- This happens when several genes within a cell change or mutate.

- Mutations occur in all of us all the time; indeed, without mutations, evolution would not occur.

- Most of the time, these mutations come to nothing as they are repaired, or do not change the function of a cell, but occasionally they cause the cell to go wrong and develop into cancer.

- Genetic changes, or mutations, may result from environmental or lifestyle factors, such as exposure to sunlight (ultraviolet radiation) or carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) or they may be inherited (from one or both parents).

- However, having an inherited gene alteration does not always mean that cancer will develop, just that the risk of developing cancer is increased.

- Most forms of cancer are sporadic, meaning that there is no inherited cause of the cancer.

Are there any known causes of cancer

- For an increasing number of human cancers, a cause has been identified.

- Some of the known risk factors include smoking (lung cancer), certain viruses (cervical cancer) and ultra-violet sunlight (skin melanoma).

- In addition, certain genes that are present in families have been identified.

- Cancer results when changes occur in genes that control normal cell division and death.

- Substances that cause DNA mutations are called mutagens.

- Mutagens that cause cancer are called carcinogens.

- In dogs and cats, there are only a few known risk factors for cancer.

- In cats, infection with feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) can be a trigger for some types of cancer (lymphoma and leukaemia).

- However, not all cats that are infected with FeLV will develop cancer and, conversely, not all lymphomas in cats are induced by FeLV infection.

- Another example of a cancer, for which there is a known cause, occurs in white-faced cats that are exposed to a lot of sun.

- The relatively hairless pink areas of the ear tips, eyelids and nose are prone to sunburn.

- As a result of excessive exposure to the sun, this can progress to a type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma.

What is the link between genes and cancer

- In people, there are a number of recognised syndromes where there is an inherited predisposition to cancer, often due to a defect in a gene that protects against tumour formation. Examples include:

- Certain inherited mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 that are associated with an elevated risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer

- Individuals with Down syndrome have an extra chromosome 21 and are known to develop malignancies such as leukaemia and testicular cancer.

- In veterinary medicine, we are still looking to identify … have we found any? What about the obesity gene in Labs and flat coats – perhaps leading to cancer?

Why has my pet developed cancer

As in human medicine, we often cannot explain why one pet develops cancer and another does not. Research has shown that certain risk factors increase the chance that a person will develop cancer. It is likely that many of the most common risk factors for cancer in people also affect our pets, including age, sunlight (ultraviolet radiation), certain chemicals, some viruses, certain hormones, poor diet, lack of physical activity, being overweight or a family history of cancer. Current research is looking at methods of identifying specific causes of cancers in dogs and cats, and this may lead to novel ways of treating them. More importantly, as the specific causes become known, specific ways of preventing that cancer may be possible.

While many of these risk factors avoided, several factors may act together over time to cause normal cells to become cancerous. When thinking about the risk of cancer remember that not everything causes cancer. Having one or more risk factors does not mean that an individual will get cancer. Some individuals are more sensitive than others to the known risk factors.

One of the most important risk factors for cancer is growing older. Most cancers occur in older pets although pets of all ages can get cancer. This means that as our pets are living longer, the incidence of cancer is rising. It is now estimated that 1 in every 2 people will be affected by cancer in their lifetime although more people are more likely to survive cancer now than ever before. It has been reported that about 1 in every 2 or 3 dogs and about 1 in 4 or 5 cats may be affected by cancer in their lifetime. In the 2004 purebred dog health survey, 1 in 4 dogs died due to cancer from 1994 to 2004 (http://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/). The median age of diagnosis of cancer was 8 years in a survey of 36,006 live dogs with 22,504 conditions in total. The median age at death due to cancer was 10½ years in a survey of cause of death for 15,881 dogs from 1994 to 2004.

In a survey of cause of death in UK cats, cancer was the second most common cause of death after trauma overall and most common reason for euthanasia (Pang and Argyle 2016) 32% of cats over 10 years will die of cancer 1 in 3 dogs will develop cancer.

Is cancer related to breed and why does cancer affect certain breeds more than others

Certain breeds of dog appear to be susceptible to specific tumours (see table below). This may be related to the characteristics of the breed or due to a genetic predisposition. However, most cancers are not inherited and truly hereditary cancers (those that are passed down in certain family lines) tend to be rare in dogs.

Bone cancer is more common in giant and large breeds such as Great Danes, Irish Wolfhounds, Rottweilers, and St Bernards. This is thought to be related to the rapid growth characteristics of the adolescent pup although there is also evidence for a genetic susceptibility in some of the giant breeds.

Boxers have a higher incidence of skin and brain tumours. Bernese mountain dogs suffer from a variety of malignant cancers that tend to affect a younger age group than other dogs as a whole. Similarly, Flat-coated Retrievers tend to have a relatively high incidence of sarcomas that behave more aggressively than in other breeds of dog. These and other breed related tumours such as mast cell tumours in golden retrievers are highly suggestive of a widespread genetic susceptibility for the specific cancer associated with the breed.

Type of cancer |

Breeds with an elevated risk of developing this cancer |

|

Histocytic sarcoma or Malignant Histiocytosis |

Bernese mountain dog, flat-coated retrievers |

|

Osteosarcoma (bone cancer) |

Large breeds such as Rottweiler, great Dane, Irish wolfhound, greyhound, Saint Bernard, Doberman, German shepherd, Irish setter, golden retriever, Borzoi, Leonberger |

|

Haemangiosarcoma (blood vessel tumours) |

German shepherd, golden retriever. |

|

Mast Cell Tumour (Skin tumours) |

boxer, bull dog, bullmastiff, Boston terrier, Staffordshire bull terrier, Rhodesian ridgeback, Weimarana, Labrador retriever, beagle, golden retriever |

|

Lymphoma/leukaemia |

boxer, bull mastiff, basset hound, Saint Bernard, Scottish terrier Airedale terrier, Bouvier des Flandres, Labrador retriever, |

|

Melanoma |

Chow Chow, golden retriever, Pekingese, poodle, Schnauzer, Scottish terrier, cocker spaniel |

|

Mammary tumours |

poodles, spaniels, Puli, English setter, pointer, dachshund, German shepherd, Maltese terrier, Yorkshire terrier |

|

Brain tumour |

golden retriever, boxer |

Adapted from Dobson J (2013), IRSN Vet Sci 2013, 941275, Published online Jan 17, 2013, doi: 10.1155/2013/941275 available at

as Open Access.

Why does cancer affect certain breeds more than others?

Most cancers develop as a result of changes in genes (mutations). A normal cell may become a cancer cell after a series of gene changes occur. Some gene changes that increase the risk of cancer are passed from parent to offspring. These changes are present at birth in all cells of the body. While it is uncommon for cancer to run in a family, certain types of cancer do occur more often in some families than in the rest of the population. For example, cancers of the breast, ovary, prostate, and colon in people. Several cases of the same cancer type in a family or line of pedigree dogs may be linked to inherited gene changes, which may increase the chance of developing cancers. However, environmental factors may also be involved.

If you think your pet may have a pattern of a certain type of cancer in the line, you may want to talk to your veterinary surgeon about ways to detect cancer early should it develop in your pet. You may also want to ask about genetic testing. These tests can check for certain inherited gene changes that increase the chance of developing cancer. However, inheriting a gene change does not mean that your pet will definitely develop cancer. It means that your pet has an increased chance of developing the disease.

What is screening for cancer

- Some types of cancer can be found before they cause clinical signs.

- Checking for cancer (or for conditions that may lead to cancer) in individuals who do not have signs is called screening.

- Screening means testing for early stages of a disease before an individual has any clinical signs or symptoms.

- Screening tests are not perfect and have some risks.

- For screening to be useful the tests need to:

- Be reliable at picking up cancers or abnormalities that could lead to cancer

- Do more good than harm to individuals being tested (i.e. potential benefits outweigh the risks).

- The UK has 3 screening programmes for people:

- Bowel cancer screening using the faecal occult blood test

- Breast cancer screening using mammography

- Cervical cancer screening using smear tests for a virus called high risk human papilloma virus (HPV)

Screening may help your vet find and treat some types of cancer early. Generally, cancer treatment is more effective when the disease is found early. However, there is currently no effective genetic or blood test that is a reliable screening tool for the diagnosis of cancer in dogs. Regular physical examinations, laboratory testing and imaging studies are the best tools that vets have for the early diagnosis of cancer. Most vets recommend annual or biannual health checks for your pet although this will vary be breed and age of your pet. These will help identify any abnormal growths as early as possible. Also, as the pet owner, you are the person who knows your pet best and if you feel that there is just something that is not quite right about your pet, be persistent in getting a diagnosis.

An important area of current research uses dogs that are trained to detect disease in people. This is based on the dogs’ ability to detect minute odour traces created by diseases. Dogs can identify cancer in urine samples from people and we hope that one day this may be applied to the diagnosis of cancer in our pet animals species (www.medicaldetectiondogs.org.uk). There are also some studies currently taking place to use cancer detection dogs to detect cancer in our pet dogs. One study is taking urine samples from healthy dogs without urinary tract abnormalities and from dogs with urinary transitional cell carcinoma or non-malignant urinary tract disease to see if the detection dogs can identify the samples with cancer.

What is a risk factor

A risk factor is something that is associated with an increased risk of disease or death. However, a risk factor is not necessarily a cause of disease. Just because a cancer is associated with something doesn’t mean it is the cause. For example, being old cannot be said to cause cancer, but older pets are more at risk of developing cancer because they have experienced more cell damage and exposure to potential carcinogens during their lifetime. Having a risk factor does not mean that your pet will get cancer just as not having a risk factor does not mean that your pet will not get a cancer

What does risk mean

Researchers describe risk as the estimated chance of developing a disease during a certain time period, such as within the next 5 years or during a lifetime. People perceive risk as the probability of something happening, such as their pet developing cancer.

Most people are concerned about the chances of their pet developing cancer as an individual or personal risk. What you consider your pet’s personal risk may be influenced by what you have heard from your veterinary surgeon, the media and from your family and friends. Many people view their pet’s risk of developing cancer as being higher or lower than it is due to the influence of these various sources of information.

How do veterinary surgeons, researchers and doctors think about risk

When veterinary surgeons talk about risk they are thinking about numbers.

Cancer risk in people is based on numbers of reports of cancer from medical facilities into a central registry. These reports count the total number of people who are diagnosed with a cancer in the United Kingdom. In veterinary medicine, there are very few sources of accurate information about cancer prevalence/incidence estimates in animals as we do not have an animal cancer registry and prospective cohort studies are very expensive and rarely carried out.

Human cancer registries also provide information about how many men or women are diagnosed, and their age and race and response to treatment. The risk numbers that come from these types of information may be presented as relative risk (RR) or absolute risk (AR). In human medicine, clinical trials are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and there is much more information available than in veterinary medicine.

Veterinary surgeons can look at exposure factors that may affect cancer risk using observational studies. They draw conclusions about how these and other specific factors affect cancer risk by looking at groups of animals who have a certain risk factor and those who do not. Veterinary surgeons then look at how many individuals in the two groups are diagnosed with cancer. By comparing how many animals in each of these groups develop cancer, veterinary surgeons are able to estimate relative risk (RR) – that is the risk that one group will get cancer compared to another group. This type of research is becoming increasingly more available for pets with more and more peer-reviewed scientific publications coming out all the time.

Veterinary surgeons can study exposure factors that may affect cancer risk using cross-sectional and longitudinal observational studies. This type of research is becoming increasingly more available for pets with more and more peer-reviewed scientific publications coming out all the time. Ideally these will be followed up with clinical trials to test different treatments for specific cancer types

How is the effect of a risk factor in an observational study expressed

The effect of a risk factor is often expressed as a relative risk (RR). In epidemiology (the study of health and disease status in populations of animals or people rather than individual animal medicine), relative risk is the risk of developing a disease relative to exposure to a risk factor. Relative risk is expressed as a ratio of the probability of disease occurring in a group exposed to a certain risk factor compared to the probability of disease occurring in a group not exposed to the same risk factor. Exposure may mean being exposed to a pesticide, being a certain breed or having been vaccinated with a particular antigen (as part of a pathogen or disease causing agent). Another term for the relative risk is the risk ratio: it is the ratio of the risk in the exposed group or population divided by the risk in the unexposed group or population. For example, a RR of 3.0 for lung cancer associated with smoking in a study means that smokers were 3 times more likely than non-smokers to develop lung cancer. While a RR of 3 sounds high, the absolute risk is 1 case of lung cancer for every 10,000 smokers and this is very small.

How is the effect of a risk factor in a survival study

In a study that looks at the survival of cases with a disease, it is the time to event (death or recurrence of disease) that is the focus. Using the statistical methods of survival analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) is estimated instead of the RR and average or median survival times can be compared between those individuals exposed to one treatment compared to another treatment. Median survival time (MST) is the time, often expressed as the number of days, months or years, when 50% of the patients are still alive. MST s can be used to compare individuals exposed to one treatment compared to another treatment or no treatment.

One study that used survival analysis for cats with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) showed that whether the cat received non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) therapy after surgery was associated with survival. The hazard ratio was 2.2 (95% confidence interval: 4.8 – 10.2), meaning that a cat that did not receive post-operative NSAID therapy was more than twice as likely to die earlier due to its tumour than cats that did receive a NSAID. This HR is an important estimate of the prognosis for a cat with an OSCC.

What are cancer statistics

- When we talk about cancer we often use big words such as prevalence, incidence and survival.

- Prevalence is the total number of cases at any one time.

- Incidence is the number of newly diagnosed cases during a specific time period.

- Mortality is the number of deaths during a specific time period, sometimes expressed as a proportional mortality rate. Mortality can also be expressed as a case fatality rate.

- Survival is the proportion of patients alive at some point after the diagnosis of their cancer.

- Lifetime risk is the probability of developing or dying from cancer, in the course of one’s lifespan.

- Median survival time (MST) is the period of time that has passed by which 50% of the affected individuals have died due to their disease.

- Absolute risk is the proportion of individuals affected usually expressed as a % or the number of individuals experiencing an event in relation to the population at risk

- Relative risk (RR) is a comparison between two groups of individuals based on exposure to a risk factor to and is usually expressed as a ratio of the two proportions.

*Cancer statistics explained using an example from the 2004 Kennel Club Survey

Cancer was reported to have been diagnosed in 646 of 36,006 or 1.8% of live dogs in the 2004 KC survey of purebred dog health. The relative risk (RR) for cancer in flatcoated retrievers was 2.1; meaning flatcoats were more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with cancer compared to all other pedigree dogs included in the survey. A total of 27% (4228/15,881) of dogs were reported to have died due to cancer from 1994 to 2003.